Building a Local, Privacy‑First RAG Pipeline with LangChain: From Embeddings to Hybrid Retrieval

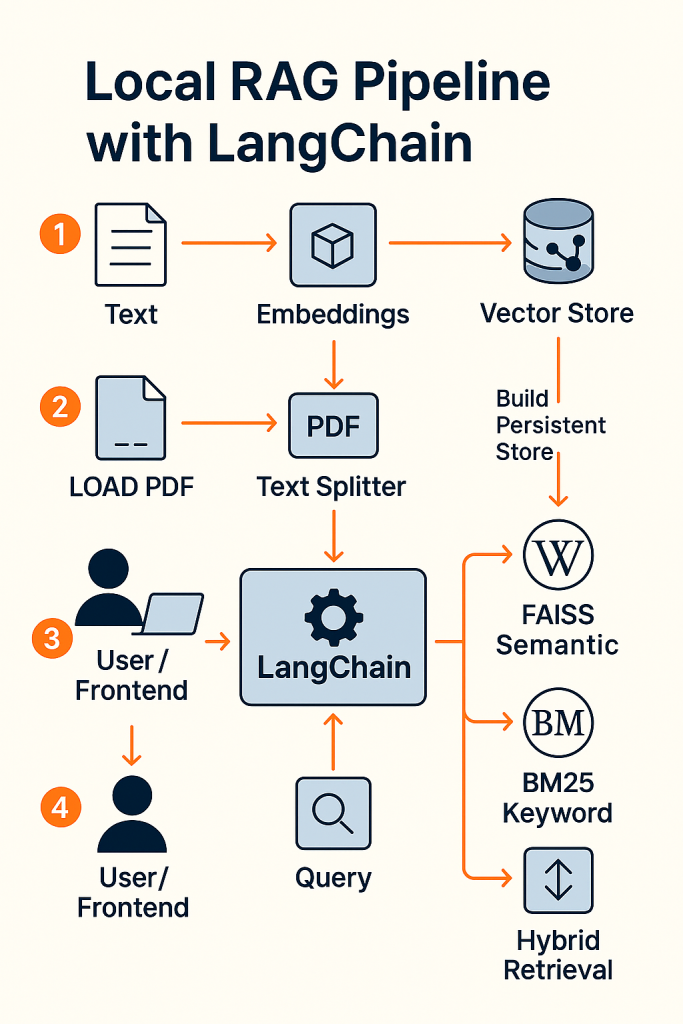

As part of my broader project to build a completely local, privacy‑first AI assistant, I’ve been exploring how to design a robust Retrieval‑Augmented Generation (RAG) pipeline using LangChain, LangGraph, and local LLMs. My goal is to create a model‑agnostic system that runs entirely on‑device, supports multimodal inputs, and uses a persistent vector store for fast, repeatable retrieval.

This notebook represents a major milestone in that journey. It walks through the full lifecycle of building a RAG system—from embedding text, to loading and chunking documents, to constructing a persistent FAISS vector store, to hybrid retrieval strategies that combine semantic and keyword search. The entire workflow is implemented using local models (Qwen embeddings) and open‑source components.

All code for this workflow is available in the public GitHub repository. I encourage you to clone it, run the notebook end‑to‑end, and contribute improvements or extensions.

github repo

The full notebook with all the steps, is available here:

RAG-techniques-LangChain

Clone the repo, open the Jupyter notebook, and step through the code.

Notebook Step by Step Walkthrough

Text Embedding with Qwen Model¶

This cell demonstrates how to use the Qwen3-Embedding model for text embeddings through LangChain’s HuggingFace integration.

Setup¶

We initialize a text embedder using the Qwen/Qwen3-Embedding-0.6B model, which is a compact 0.6 billion parameter embedding model. This embedder will convert text into dense vector representations that can be used for:

- Semantic search

- Text similarity comparison

- Document retrieval

- Clustering and classification tasks

The HuggingFaceEmbeddings class provides a simple interface to load and use the model with default configurations.

from langchain_huggingface import HuggingFaceEmbeddings

import torch

text_embedder = HuggingFaceEmbeddings(

model_name="Qwen/Qwen3-Embedding-0.6B"

)

d:\Code\LangChain-RAG\.venv\Lib\site-packages\langchain_core\_api\deprecation.py:26: UserWarning: Core Pydantic V1 functionality isn't compatible with Python 3.14 or greater. from pydantic.v1.fields import FieldInfo as FieldInfoV1 d:\Code\LangChain-RAG\.venv\Lib\site-packages\tqdm\auto.py:21: TqdmWarning: IProgress not found. Please update jupyter and ipywidgets. See https://ipywidgets.readthedocs.io/en/stable/user_install.html from .autonotebook import tqdm as notebook_tqdm

Text Embedding Generation¶

In the cell below, we define a list of sample texts and generate embeddings for them:

Sample Texts: We create a list of 4 sentences covering two semantic topics:

- Weather-related sentences (about sunny days)

- Food-related sentences (about pizza)

Embedding Generation: We use the

embed_documents()method of our text embedder to convert all texts into vector representations simultaneously.Output: The code prints each embedding vector and displays:

- The total number of embeddings generated (should be 4, one per text)

- The embedding dimension (1024 for the Qwen3-Embedding-0.6B model)

Expected Result: Semantically similar texts (e.g., the two weather sentences or the two pizza sentences) should have embeddings that are closer together in the vector space, which can be useful for similarity comparison and clustering tasks.

texts = [

"The sky is clear and the sun is shining brightly",

"It is a sunny day with no clouds in sight.",

"I am craving a slice of pizza for dinner tonight.",

"I feel like eating pizza this evening."

]

embeddings = text_embedder.embed_documents(texts)

for i, embedding in enumerate(embeddings):

print(f"Text {i+1} embedding: {embedding}")

print(f"Total embeddings generated: {len(embeddings)}")

print(f"Embedding dimension: {len(embeddings[0])}")

Text 1 embedding: [-0.013901935890316963, -0.016430605202913284, -0.002654974116012454, 0.01667698659002781, ...] Text 2 embedding: [-0.0180942602455616, -0.020602528005838394, -0.003632498439401388, -0.016885682940483093, ...] Text 3 embedding: [-0.025657763704657555, 0.024037810042500496, -0.002704175654798746, -0.022849055007100105, ...] Text 4 embedding: [-0.02188185043632984, 0.03758257254958153, -0.0023960028775036335, -0.019942952319979668, ...] Total embeddings generated: 4 Embedding dimension: 1024

PDF Document Loading¶

In the cell below, we load a PDF document using LangChain’s PyPDFLoader:

PDF Loader Initialization: We create a

PyPDFLoaderinstance pointing to a PDF file about General Astronomy from Wikibooks located atbooks/general-astronomy-wikibooks.pdf.Document Loading: The

load()method extracts all pages from the PDF and converts them into a list ofDocumentobjects. EachDocumentcontains:page_content: The text content extracted from that pagemetadata: Information about the page including producer, page number, and page label

Output: The code displays:

- The total number of pages loaded from the PDF

- The complete text content of the first page (index 0)

- The metadata of the first page (including PDF producer info, page number, etc.)

- The text content of the 100th page (index 99) to demonstrate access to later pages

Expected Result: This will show how PDF documents are structured in LangChain, with each page becoming a separate document that can be processed, embedded, or used for retrieval tasks. The astronomy textbook should contain several hundred pages of content about astronomical topics.

from langchain_community.document_loaders.pdf import PyPDFLoader

pdf_loader = PyPDFLoader("books/general-astronomy-wikibooks.pdf")

document = pdf_loader.load()

print(f"Total pages loaded: {len(document)}\n\n")

print(f"Content of first page:\n{document[0].page_content}\n\n")

print(f"Metadata of first page:\n{document[0].metadata}\n\n")

print(f"Content of the 100th page:\n{document[99].page_content}\n\n")

d:\Code\LangChain-RAG\.venv\Lib\site-packages\langchain_core\_api\deprecation.py:26: UserWarning: Core Pydantic V1 functionality isn't compatible with Python 3.14 or greater. from pydantic.v1.fields import FieldInfo as FieldInfoV1 d:\Code\LangChain-RAG\.venv\Lib\site-packages\tqdm\auto.py:21: TqdmWarning: IProgress not found. Please update jupyter and ipywidgets. See https://ipywidgets.readthedocs.io/en/stable/user_install.html from .autonotebook import tqdm as notebook_tqdm

Total pages loaded: 341

Content of first page:

General Astronomy

en.wikibooks.org

Metadata of first page:

{'producer': '3-Heights™ PDF Optimization Shell 6.3.1.5 (http://www.pdf-tools.com)', 'creator': 'LaTeX with hyperref package', 'creationdate': '2015-03-15T13:10:03+01:00', 'moddate': '2023-10-09T20:27:12+00:00', 'source': 'books/general-astronomy-wikibooks.pdf', 'total_pages': 341, 'page': 0, 'page_label': 'I'}

Content of the 100th page:

Motion and Gravity

and the first to imagine an underlying order in nature — though no real connection between

human and celestial events existed, the prophecies of astrology were the ancestors of modern

scientific prediction.

The early astronomers understood a great deal about the world around them. By Aristotle’s

time, many people believed that the world was round. They knew this from several sources

of evidence:

1. When ships sailed beyond the horizon, those watching from land would see the hull

disappear first, and then would watch the sail disappear. Sailors see the land sink

below the horizon bottom-first. From this, they gathered that the surface of the world

was curved, and that the ship was moving around the curvature of the Earth.

2. Ancient people supposed eclipses of the Moon to be the shadow of the Earth. Shadows

seen during lunar eclipses were always round. The only shape that always casts a

round shadow is a sphere. This suggested that the Earth was spherical.

3. Travelers noticed that new stars became visible as they moved in their journeys. When

travelers move north, the North Star and the northern constellations gain altitude in

the sky. The ancients recognized that this implied that the Earth is curved.

Aristotle mentions in his writings that some thinkers of his time hold that the Earth is flat,

while others believe it to be spherical. He himself argues firmly that the Earth is a sphere.

After Aristotle’s time, nearly all Western writers claim that the Earth is a sphere.

92

Document Chunking with Text Splitter¶

In the cell below, we split the loaded PDF document into smaller, manageable chunks using LangChain’s CharacterTextSplitter:

Text Splitter Configuration: We initialize a

CharacterTextSplitterwith specific parameters:separator = "\n": Splits text at newline characters to preserve natural paragraph boundarieschunk_size = 1000: Each chunk will contain approximately 1000 characterschunk_overlap = 100: Adjacent chunks will overlap by 100 characters to maintain context continuity across boundaries

Document Splitting: The

split_documents()method processes all pages from the loaded PDF document and breaks them into smaller chunks based on the configured parameters.Output: The code displays:

- The total number of chunks created from the entire PDF

- The content of the 50th chunk (index 49)

- The content of the 51st chunk (index 50) to demonstrate the overlap between consecutive chunks

Why Chunking?: Breaking documents into smaller chunks is essential for:

- Embedding Generation: Most embedding models have token limits and work better with shorter text segments

- Semantic Search: Smaller chunks allow more precise retrieval of relevant information

- Context Management: Chunks can fit within the context window of language models for question-answering tasks

- Memory Efficiency: Processing smaller pieces reduces computational requirements

Chunk Overlap: The 100-character overlap ensures that information spanning chunk boundaries isn’t lost and maintains semantic continuity between adjacent chunks.

from langchain_text_splitters import CharacterTextSplitter

text_splitter = CharacterTextSplitter(

separator = "\n",

chunk_size = 1000,

chunk_overlap = 100

)

chunks = text_splitter.split_documents(document)

print(f"Total chunks created: {len(chunks)}\n\n")

print(f"Content of the 50th chunk:\n{chunks[49].page_content}\n\n")

print(f"Content of the 51st chunk:\n{chunks[50].page_content}\n\n")

Total chunks created: 876 Content of the 50th chunk: the Virgo Cluster. It orbits near the edge of the Cluster, so we can see much of its center in a small region of the sky in the direction of the constellation Virgo. Presently, the Milky Way is moving away from the center of Virgo Cluster. In the distant future, however, the Cluster’s pull will slow the Milky Way and draw it inward. Although our reach now includes many more objects, the size scale of galaxy clusters still does not represent an expansion over the last size scale by a factor of 1000. We have not fully reached the next step in our journey until we come to the scale of hundreds of millions of light years. At this scale, even the galaxy clusters form clusters. These groups of galaxy clusters are called superclusters . A supercluster may contain hundreds of thousands of galaxies. The Virgo Cluster is a member of a supercluster called the Virgo Supercluster. Light from the edge of our 500 million light-year reach has traveled for 500 million years Content of the 51st chunk: Light from the edge of our 500 million light-year reach has traveled for 500 million years before reaching us. This means that we see the Virgo Supercluster as it was 500 million years ago. Five hundred million years can be a long time, but it isn’t really long enough for the universe to have changed significantly. Even though the light is old, the universe at the edge of the Virgo Supercluster still looks much like the universe nearby. 8

Recursive Character Text Splitter¶

In the cell below, we demonstrate an alternative and more sophisticated approach to document chunking using LangChain’s RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter:

Hierarchical Splitting Strategy: Unlike the simple

CharacterTextSplitterused earlier, theRecursiveCharacterTextSplitteruses a hierarchical list of separators:"\n\n": First tries to split on double newlines (paragraph breaks)"\n": If chunks are still too large, splits on single newlines" ": If still too large, splits on spaces (word boundaries)"": As a last resort, splits on individual characters

Smart Splitting Logic: The splitter recursively attempts each separator in order, using the first one that produces chunks within the desired size. This preserves document structure better than a single-separator approach.

Configuration Parameters:

chunk_size = 1000: Target size of 1000 characters per chunkchunk_overlap = 100: 100-character overlap between adjacent chunks for context continuity

Document Processing: The same PDF document is re-split using this more intelligent strategy, which should produce chunks that respect natural text boundaries more effectively.

Output Comparison: The code displays:

- Total number of chunks created (may differ from the

CharacterTextSplitterresult) - Content of the 50th and 51st chunks for comparison with the previous splitting method

- Total number of chunks created (may differ from the

Advantages of Recursive Splitting: This approach produces more semantically coherent chunks by:

- Preserving paragraph boundaries when possible

- Avoiding mid-sentence splits in most cases

- Maintaining better context within each chunk

- Improving the quality of embeddings and retrieval results

This is generally the preferred method for splitting documents in production RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) systems.

from langchain_text_splitters import RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter

text_splitter = RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter(

separators = ["\n\n", "\n", " ", ""],

chunk_size = 1000,

chunk_overlap = 100

)

chunks = text_splitter.split_documents(document)

print(f"Total chunks created: {len(chunks)}\n\n")

print(f"Content of the 50th chunk:\n{chunks[49].page_content}\n\n")

print(f"Content of the 51st chunk:\n{chunks[50].page_content}\n\n")

Total chunks created: 877 Content of the 50th chunk: the Virgo Cluster. It orbits near the edge of the Cluster, so we can see much of its center in a small region of the sky in the direction of the constellation Virgo. Presently, the Milky Way is moving away from the center of Virgo Cluster. In the distant future, however, the Cluster’s pull will slow the Milky Way and draw it inward. Although our reach now includes many more objects, the size scale of galaxy clusters still does not represent an expansion over the last size scale by a factor of 1000. We have not fully reached the next step in our journey until we come to the scale of hundreds of millions of light years. At this scale, even the galaxy clusters form clusters. These groups of galaxy clusters are called superclusters . A supercluster may contain hundreds of thousands of galaxies. The Virgo Cluster is a member of a supercluster called the Virgo Supercluster. Light from the edge of our 500 million light-year reach has traveled for 500 million years Content of the 51st chunk: Light from the edge of our 500 million light-year reach has traveled for 500 million years before reaching us. This means that we see the Virgo Supercluster as it was 500 million years ago. Five hundred million years can be a long time, but it isn’t really long enough for the universe to have changed significantly. Even though the light is old, the universe at the edge of the Virgo Supercluster still looks much like the universe nearby. 8

Semantic Chunking¶

In the cell below, we demonstrate an advanced, intelligent approach to document chunking using LangChain’s SemanticChunker:

Semantic-Based Splitting: Unlike character-based or recursive text splitters that rely on fixed separators and character counts, the

SemanticChunkeruses embeddings to understand the semantic meaning of the text and splits documents based on semantic similarity between sentences.How It Works:

- The splitter generates embeddings for consecutive sentences in the document

- It calculates semantic similarity between adjacent sentences

- When the similarity drops below a threshold (indicating a topic shift), it creates a new chunk

- This ensures each chunk contains semantically coherent content about a single topic

Embedding Model: Uses the Qwen/Qwen3-Embedding-4B model, a larger and more powerful 4 billion parameter embedding model (compared to the 0.6B model used earlier), which provides:

- Higher quality semantic representations

- Better understanding of context and meaning

- More accurate detection of topic boundaries

Configuration Parameters:

embeddings = embedding_model: The HuggingFace embedding model to use for semantic analysisbuffer_size = 1: Number of sentences to consider when calculating semantic breaks (1 means comparing consecutive sentences)add_start_index = True: Adds metadata tracking the starting character position of each chunk in the original document

Document Processing: The same astronomy PDF document is split using semantic understanding rather than fixed rules.

Advantages of Semantic Chunking: This approach produces the highest quality chunks by:

- Respecting Topic Boundaries: Splits occur naturally where topics change, not at arbitrary character counts

- Maintaining Semantic Coherence: Each chunk discusses a single coherent topic or concept

- Variable Chunk Sizes: Chunks can be longer or shorter based on natural content boundaries

- Improved Retrieval Quality: Better semantic coherence leads to more accurate search and retrieval results

Trade-offs:

- Computational Cost: Requires generating embeddings for the entire document, which is more resource-intensive

- Processing Time: Slower than character-based splitting methods

- Dependencies: Requires a good embedding model and sufficient compute resources

This method is ideal for production RAG systems where retrieval quality is paramount and computational resources are available.

from langchain_experimental.text_splitter import SemanticChunker

from langchain_huggingface import HuggingFaceEmbeddings

import torch

embedding_model = HuggingFaceEmbeddings(

model_name = "Qwen/Qwen3-Embedding-4B"

)

text_splitter = SemanticChunker(

embeddings = embedding_model,

buffer_size = 1,

add_start_index = True

)

chunks = text_splitter.split_documents(document)

Loading checkpoint shards: 100%|██████████| 2/2 [00:01<00:00, 1.09it/s]

print(f"Total chunks created: {len(chunks)}\n\n")

print(f"Content of the 500th chunk:\n{chunks[499].page_content}\n\n")

print(f"Content of the 501st chunk:\n{chunks[500].page_content}\n\n")

Total chunks created: 1092 Content of the 500th chunk: This means that the Earth makes a little more than a full rotation over the course of a solar day. A sidereal day is the amount of time it takes for the stars to go once around the sky, equal to 23 hours and 56 minutes. The word sidereal means ”relating to the stars.” The difference in length between the solar and sidereal day causes the rising and setting times of stars to change throughout the year. If the star Rigel, for example, rises at noon today, it will rise at 11:56 tomorrow. In six months, it will rise at midnight. Because the difference between solar days is tied to the orbit of the Earth, there is exactly one more sidereal day in a year than there are solar days. 57 Content of the 501st chunk: Observational Astronomy Figure 30 A sidereal month is the period of the moon in relation to the stars; approximately 27 (1/3) days (13 degrees a day). Ancient peoples used this period to track time, as evidenced by the Big Horn Medicine Wheel in Sheridan, Wyoming.

FAISS Vector Store Creation and Semantic Search¶

In the cell below, we create a vector database using FAISS (Facebook AI Similarity Search) and perform semantic search on our astronomy document:

Embedding Model Initialization: We create a new instance of

HuggingFaceEmbeddingsusing the Qwen/Qwen3-Embedding-0.6B model (the smaller, faster embedding model) for generating vector representations of our document chunks.Vector Store Creation: We use

FAISS.from_documents()to:- Take all the semantically-chunked documents from the previous step

- Generate embeddings for each chunk using the embedding model

- Build a FAISS index that enables fast similarity search across all chunks

- Store the entire vector database structure in memory

Persistent Storage: The

save_local("faiss_index")method saves the vector store to disk in a directory called “faiss_index”, allowing us to reload it later without re-processing the entire document.Semantic Search Setup: We convert the vector store into a retriever with:

search_kwargs={"k": 5}: Configured to return the top 5 most relevant chunks for any query

Query Execution: We perform a semantic search with the question “What is the distance from the Earth to the Sun?”:

- The query is converted into an embedding

- FAISS finds the 5 document chunks with embeddings most similar to the query

- Results are ranked by semantic similarity

Results Display: The code prints all 5 retrieved chunks, showing the content that the system determined to be most relevant to answering the distance question.

GPU Memory Management: After processing, the code clears CUDA memory if a GPU was used, freeing resources for subsequent operations.

How FAISS Works: FAISS uses efficient algorithms to quickly search through millions of high-dimensional vectors, making it ideal for retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) systems where we need to find relevant context from large document collections.

from langchain_community.vectorstores import FAISS

from langchain_huggingface import HuggingFaceEmbeddings

import torch

embedding_model = HuggingFaceEmbeddings(

model_name = "Qwen/Qwen3-Embedding-0.6B"

)

vector_store = FAISS.from_documents(

documents = chunks,

embedding = embedding_model

)

vector_store.save_local("faiss_index")

query = "What is the distance from the Earth to the Sun?"

vector_retriever = vector_store.as_retriever(search_kwargs={"k":5})

results = vector_retriever.invoke(query)

print(f"Top 5 results for the query '{query}':\n\n")

for i, result in enumerate(results):

print(f"Result {i+1} content:\n{result.page_content}\n\n")

#clear gpu memory

if torch.cuda.is_available():

torch.cuda.empty_cache()

Top 5 results for the query 'What is the distance from the Earth to the Sun?': Result 1 content: Sun at distances between approximately 0.3 and 1.5 Astronomical Units from the Sun (an Astronomical Unit or AU is defined as the average distance between the Earth and the Sun, so the Earth is 1 A. U. from the Sun). In contrast, the Jovian planets spread from 5AU to 30 AU. The terrestrials are fairly small; the Earth is the largest of the four, and Mercury is only about 1/4 the diameter of the Earth. The Jovians are relatively large, from 4 to 11 times the size of the Earth. All of the terrestrial planets are presumed to have formed through the same process, so all should share common properties. The terrestrial planets are different than the Jovians because a planet close to a star forms under different conditions than if it is far from the star. The terrestrial planets formed separately in different orbits, so there are significant differences between the four. The four terrestrials have many things in common, but each Result 2 content: second. This distance, the distance light travels in one second, is called a light-second . Figure 3 This mosaic image of the Sun and six planets was taken by the Voyager spacecraft from beyond the planets. Earth is barely visible as a blue dot in one of the frames, almost lost in the glare from sunlight. The Voyager spacecraft, which view the orbits of the planets from outside, are the most distant man-made objects from Earth. Notice that the two terrestrial planets, Venus and Earth, are much nearer the Sun than the others. Another step out will give us reach to most of the planets. We now encompass the bulk of the Solar System , the system comprising the Sun and all of the objects orbiting around it. This size scale is about five billion kilometers across, 30 times the distance between the Earth and the Sun. The distance from the Earth to the Sun is a convenient standard for measurement in the Solar System, so astronomers use the average Earth-Sun distance as Result 3 content: measurement in the Solar System, so astronomers use the average Earth-Sun distance as a standard unit called the astronomical unit (AU) . One astronomical unit is equal to about 93 million miles or 150 million kilometers. We can say that we are now working at a size scale of 30 astronomical units, or 30 AU for short. A box this size centered on the Earth will comfortably fit Saturn’s orbit, but Uranus, Neptune and Pluto are still too far away. For much of human history, none of the Solar System objects outside of this box were known to exist. Remember that our size scale has increased from the last step by a huge factor, a factor of 1000. Using our jet to take a trip from Earth to Saturn would take about fifty years. Light takes about 80 minutes to travel from Saturn to Earth, depending on where Earth and Saturn are in their orbits. Because it takes so long for light to make the trip from Saturn, the light we see from the planet at a given moment actually left 80 minutes ago. Result 4 content: system is surrounded by huge expanse of empty space. This view is only a small piece of the fifth step in our journey, and Earth is already becoming very tiny. As we continue to move out, we reach a size of about 1000 times the size of the Earth. The distance to the Moon is about 30 times the diameter of Earth, so the Moon is easily within reach in this step, but there’s little else in the remaining distance. The nearest planets, Mars and Venus, are out of our reach. Aside from the Earth and Moon, we find the space in 4 Result 5 content: widely spaced orbits. The next step in our journey will encompass a distance of 30,000 AU, or half a light-year. Although this step completely encloses the planets, Solar System objects are found at much greater distances. These objects form the Oort cloud , a vast, sparse region of comets surrounding the Sun. The Oort cloud is almost empty, but it’s there just the same. At this step we’ve only covered a piece of the range of influence of the Sun, and plenty of Oort cloud remains out of our reach. The Oort cloud is thought to extend out from the Sun as much as two light-years. If we look just beyond this step, we find the nearest star, Proxima Centauri, at about four light-years. It will take Voyager 1 and 2 80,000 years to reach this star. (These ships, launched in 1977, have a speed of 51,500 km/hour.) As other stars enter into the picture, the Sun will no longer be the dominant source of gravity. This means that we can expect

Loading FAISS Vector Store from Disk¶

In the cell below, we demonstrate how to load a previously saved FAISS vector store from disk and perform a new semantic search query:

Loading the Vector Store: We use

FAISS.load_local()to reload the vector database that was saved earlier:folder_path = "faiss_index": Specifies the directory where the FAISS index was savedembeddings = embedding_model: Provides the same embedding model (Qwen3-Embedding-0.6B) used to create the original embeddingsallow_dangerous_deserialization = True: Required security flag to allow loading the serialized FAISS index (use with caution in production with untrusted data)

Retriever Configuration: The loaded vector store is converted into a retriever with

search_kwargs={"k": 5}to return the top 5 most semantically similar chunks for any query.New Query Execution: We perform a semantic search with the question “How many planets are in the solar system?”:

- The query is embedded using the same model

- FAISS searches through all 877 document chunks to find the most relevant ones

- The system returns the 5 chunks most likely to contain information about planets in our solar system

Results Display: The code prints all 5 retrieved chunks, showing the content ranked by relevance to the query about planetary count.

Advantages of Loading from Disk: By saving and loading the vector store, we avoid:

- Re-processing the entire PDF document

- Re-generating embeddings for all chunks (which can take significant time and compute resources)

- Rebuilding the FAISS index structure

This approach is essential for production systems where the document collection is preprocessed once and then queried many times, significantly improving response time and reducing computational costs.

vector_store = FAISS.load_local(

folder_path = "faiss_index",

embeddings = embedding_model,

allow_dangerous_deserialization = True

)

vector_retriever = vector_store.as_retriever(search_kwargs={"k":5})

query = "How many planets are in the solar system?"

results = vector_retriever.invoke(query)

print(f"Top 5 results for the query '{query}':\n\n")

for i, result in enumerate(results):

print(f"Result {i+1} content:\n{result.page_content}\n\n")

Top 5 results for the query 'How many planets are in the solar system?': Result 1 content: 6 Planetary science 6.1 The T errestrial Planets The Solar System consists of eight planets circling a central star - the Sun. The eight planets fall into two distinct groups. The four innermost planets are very close to the sun, are formed of rocky materials, and are relatively small. The four outermost planets are far from the Sun, are formed of gasses, and are relatively large. The Earth is one of the four innermost planets, so they are called the terrestrial planets ( Terra is latin for earth, so terrestrial means ”earth-like”. The four outer planets are called the Jovian (Jupiter-like ) planets. The terrestrial planets are, in order of distance from the Sun, Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars. All of these planets are made of rocky substances, primarily nickel, iron, and silicon. The Jovians are composed mostly of hydrogen and helium gas. The terrestrials orbit the Sun at distances between approximately 0.3 and 1.5 Astronomical Units from the Sun (an Result 2 content: Contents 5.23 Cutting Edge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 143 5.24 References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 143 6 Planetary science 145 6.1 The Terrestrial Planets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 145 6.2 Mercury . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 145 6.3 Venus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 146 6.4 Earth . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 146 6.5 Mars . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 146 6.6 The Jovian Planets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 147 6.7 The Solar System Jovians . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 147 6.8 Planetary Moons . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 148 7 Mercury 149 8 V enus 151 9 Earth 153 10 Mars 155 11 Jupiter 157 Result 3 content: 22 The Sun The Sun is the star at the center of the solar system, around which Earth, the seven other planets, and numerous other bodies revolve. It is sometimes called Sol (hence the term ”solar system”). The Sun has a mean diameter of 1.392 million kilometers, which is 109.1 times the diameter of Earth and 9.7 times the diameter of the largest planet, Jupiter. The Sun’s rotation period relative to the distant stars is 25.05 Earth-days at its equator and 34.3 Earth-days at the poles. 22.1 Solar Structure and Composition Figure 99 The Sun The sun is composed of extremely hot, gaseous material. Because of the high temperatures, this material exists in a state called plasma , in which electrons have been stripped from their parent nuclei. The Sun’s composition is roughly 90% hydrogen and 10% helium, by total numbers of nuclei. Considering mass, about 71 percent of the Sun is hydrogen, and 27 percent helium. The difference is due to the fact that helium nuclei have about 4 times the Result 4 content: Earth’s equatorial plane and the plane of the ecliptic relative to the galactic plane. The fact that the Milky Way divides the night sky into two roughly equal hemispheres indicates that the solar system lies close to the galactic plane. The Milky Way Galaxy is about 80-100 thousand light years in diameter, about 3,000 light years in thickness, and about 250-300 thousand light years in circumference. It is composed of 200 to 400 billion stars (exact number not yet known). As a guide to the relative physical scale of the Milky Way, if the galaxy were reduced to 130 km (80 mi) in diameter, the solar system would be a mere 2 mm (0.08 in) in width. The Milky Way’s absolute magnitude, which cannot be measured directly, is assumed by astronomical convention to be −20.5. 1 27.2 Types of Galaxies Estimates of the number of galaxies in the universe range from 10 billion to over 100 billion. http://hypertextbook.com/facts/1999/TopazMurray.shtml Result 5 content: 23 Stars Stars, by astronomical definition, are massive luminous balls of plasma. They exist in numbers too large to comprehend, and most are believed to be accompanied by a system of planets. The planet Earth 1 is part of the Sun 2’s solar system of 8 planets, the Sun being the nearest star to Earth. The Sun provides most of Earth’s energy, and is critical to the survival of all forms of life on the planet. Over the history of mankind, human views of the stars have differed greatly. Historically, the stars have existed as major figments in the mythological canon of many cultures, and were seen as objects of mystery and speculation. The Sun in particular has been the object of great cultural, religious and theoretical importance and speculation and has, more specifically, been a central point of debate in arguments relating to the topography and geography of the solar system itself. The stars have also been great use. Seafarers and fisherman have historically used the

Adding a New PDF Document to the Existing Vector Store¶

In the cell below, we demonstrate how to expand an existing FAISS vector store by adding documents from a second PDF:

Loading a New PDF: We load a second astronomy textbook “Our Solar System and Other Planetary Systems” by Elizabeth Bell and Edith Soto using

PyPDFLoader. The code displays the total number of pages loaded from this new PDF.Document Chunking: The new PDF is split into chunks using

RecursiveCharacterTextSplitterwith the same configuration as before:- Hierarchical separators:

["\n\n", "\n", " ", ""] chunk_size = 1000: Each chunk contains approximately 1000 characterschunk_overlap = 100: 100-character overlap between adjacent chunks

The code prints the total number of chunks created from this second document.

- Hierarchical separators:

Loading the Existing Vector Store: The previously saved FAISS index is loaded from the

"faiss_index"directory using the same Qwen3-Embedding-0.6B embedding model.Adding New Documents: The

add_documents()method appends the chunks from the new PDF to the existing vector store. This operation:- Generates embeddings for all new chunks using the same embedding model

- Adds these embeddings to the FAISS index

- Maintains all previously indexed chunks from the first astronomy PDF

Verification: The code prints the total number of documents now stored in the updated vector store using

vector_store.index.ntotal, which should equal the sum of chunks from both PDFs (original 877 chunks + new chunks from the second PDF = 1552 total).Persistent Storage: The expanded vector store is saved back to disk with

save_local("faiss_index"), overwriting the previous index file with the updated version containing both documents.

Use Case: This approach is essential for building a comprehensive knowledge base from multiple documents. Instead of creating separate vector stores for each document, we can maintain a single, unified searchable index that can retrieve relevant information from any source document based on semantic similarity to user queries.

Scalability: This pattern allows you to incrementally grow your vector database over time by adding new documents without reprocessing the entire collection.

from langchain_community.document_loaders import PyPDFLoader

from langchain_text_splitters import RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter

from langchain_community.vectorstores import FAISS

from langchain_huggingface import HuggingFaceEmbeddings

pdf_loader = PyPDFLoader("books/our-solar-system-and-other-planetary-systems-elizabeth-bell-and-edith-soto.pdf")

document = pdf_loader.load()

print(f"Total pages loaded: {len(document)}\n\n")

chunker = RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter(

separators = ["\n\n", "\n", " ", ""],

chunk_size = 1000,

chunk_overlap = 100

)

chunks = chunker.split_documents(document)

print(f"Total chunks created: {len(chunks)}\n\n")

vector_store = FAISS.load_local(

folder_path = "faiss_index",

embeddings = HuggingFaceEmbeddings(

model_name = "Qwen/Qwen3-Embedding-0.6B"

),

allow_dangerous_deserialization = True

)

vector_store.add_documents(chunks)

print(f"Total documents in the updated vector store: {vector_store.index.ntotal}\n\n")

vector_store.save_local("faiss_index")

Total pages loaded: 421 Total chunks created: 1552 Total documents in the updated vector store: 2429

Testing the Expanded Vector Store with a New Query¶

In the cell below, we verify that the expanded FAISS vector store now contains documents from both astronomy PDFs by performing a new semantic search query:

Loading the Updated Vector Store: We reload the FAISS index from the

"faiss_index"directory, which now contains chunks from both:- The original “General Astronomy” Wikibooks PDF (877 chunks)

- The newly added “Our Solar System and Other Planetary Systems” PDF (675 chunks)

- Total: 1,552 document chunks

Retriever Configuration: The vector store is converted into a retriever configured to return the top 5 most semantically similar chunks (

search_kwargs={"k": 5}).Query About Planet Types: We perform a semantic search with the question “What are the different types of planets in our solar system?” This query is specifically chosen to potentially retrieve information from the newly added second PDF, which focuses on planetary systems.

Enhanced Results Display: For each of the 5 retrieved chunks, the code prints:

- The content of the chunk (the actual text that is relevant to the query)

- The metadata source showing which PDF file the chunk came from (either the original General Astronomy book or the newly added Our Solar System book)

This dual display allows us to verify that the vector store successfully integrated both documents and can retrieve relevant information from either source.

Source Attribution: By displaying the

metadata['source']field, we can see which book each retrieved chunk originated from, demonstrating that:- The vector store properly maintains metadata when adding new documents

- Semantic search works across the entire collection regardless of source

- Results are ranked purely by relevance, not by which document they came from

Expected Outcome: The results should include information about terrestrial planets, giant planets, and possibly exoplanets (superearths) from both astronomy textbooks. The sources will show a mix of both PDF files, proving that the expanded vector store successfully combines multiple documents into a unified, searchable knowledge base.

Use Case: This pattern is essential for building comprehensive question-answering systems that can draw upon multiple authoritative sources to provide complete and accurate answers to user queries.

vector_store = FAISS.load_local(

folder_path = "faiss_index",

embeddings = embedding_model,

allow_dangerous_deserialization = True

)

vector_retriever = vector_store.as_retriever(search_kwargs={"k":5})

query = "What are the different types of planets in our solar system?"

results = vector_retriever.invoke(query)

print(f"Top 5 results for the query '{query}':\n\n")

for i, result in enumerate(results):

print(f"Result {i+1} content:\n{result.page_content}\n\n")

print(f"Result {i+1} source:\n{result.metadata['source']}\n\n")

Top 5 results for the query 'What are the different types of planets in our solar system?': Result 1 content: 6 Planetary science 6.1 The T errestrial Planets The Solar System consists of eight planets circling a central star - the Sun. The eight planets fall into two distinct groups. The four innermost planets are very close to the sun, are formed of rocky materials, and are relatively small. The four outermost planets are far from the Sun, are formed of gasses, and are relatively large. The Earth is one of the four innermost planets, so they are called the terrestrial planets ( Terra is latin for earth, so terrestrial means ”earth-like”. The four outer planets are called the Jovian (Jupiter-like ) planets. The terrestrial planets are, in order of distance from the Sun, Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars. All of these planets are made of rocky substances, primarily nickel, iron, and silicon. The Jovians are composed mostly of hydrogen and helium gas. The terrestrials orbit the Sun at distances between approximately 0.3 and 1.5 Astronomical Units from the Sun (an Result 1 source: books/general-astronomy-wikibooks.pdf Result 2 content: 129 | Our Solar System & Other Planetary Systems Pluto, Eris, Haumea, and Makemake do not fit into either category; as icy dwarf planets, they exist in an ice realm on the fringes of the main planetary system. The giant planets are composed mostly of liquids and gases. Smaller members of the solar system include asteroids (including the dwarf planet Ceres), which are rocky and metallic objects found mostly between Mars and Jupiter; comets, which are made mostly of frozen gases and generally orbit far from the Sun; and countless smaller grains of cosmic dust. When a meteor survives its passage through our atmosphere and falls to Earth, we call it a meteorite. Footnotes • 1. The generic term for a group of planets and other bodies circling a star is planetary system. Ours is called the solar system because our Sun is sometimes called Sol. Strictly speaking, then, there is only one solar system; planets orbiting other stars are in planetary systems. Result 2 source: books/our-solar-system-and-other-planetary-systems-elizabeth-bell-and-edith-soto.pdf Result 3 content: planets differ greatly in size and chemical properties. The biggest dispute concerns Pluto, which is much smaller than the other eight major planets. The category of dwarf planet was invented to include Pluto and similar icy objects beyond Neptune. But is a dwarf planet also a planet? Logically, it should be, but even this simple issue of grammar has been the subject of heated debate among both astronomers and the general public. Key Concepts and Summary Our solar system currently consists of the Sun, eight planets, five dwarf planets, nearly 200 known moons, and a host of smaller objects. The planets can be divided into two groups: the inner terrestrial planets and the outer giant planets. Result 3 source: books/our-solar-system-and-other-planetary-systems-elizabeth-bell-and-edith-soto.pdf Result 4 content: 121 | Our Solar System & Other Planetary Systems Orbits of the Planets - Figure 2. All eight major planets orbit the Sun in roughly the same plane. The five currently known dwarf planets are also shown: Eris, Haumea, Pluto, Ceres, and Makemake. Note that Pluto’s orbit is not in the plane of the planets Each of the planets and dwarf planets also rotates (spins) about an axis running through it, and in most cases the direction of rotation is the same as the direction of revolution about the Sun. The exceptions are Venus, which rotates backward very slowly (that is, in a retrograde direction), and Uranus and Pluto, which also have strange rotations, each spinning about an axis tipped nearly on its side. We do not yet know the spin orientations of Eris, Haumea, and Makemake. The four planets closest to the Sun (Mercury through Mars) are called the inner or terrestrial planets. Often, Result 4 source: books/our-solar-system-and-other-planetary-systems-elizabeth-bell-and-edith-soto.pdf Result 5 content: The recent discovery of hundreds of planets in orbit around other stars has shown astronomers that many exoplanetary systems can be quite different from our own solar system. For example, it is common for these systems to include planets intermediate in size between our terrestrial and giant planets. These are often called superearths. Some exoplanet systems even have giant planets close to the star, reversing the order we see in our system. In The Birth of Stars and the Discovery of Planets outside the Solar System, we will look at these exoplanet systems. But for now, let us focus on theories of how our own particular system has formed and evolved. Looking for Patterns One way to approach our question of origin is to look for regularities among the planets. We found, for example, that all the planets lie in nearly the same plane and revolve in the same direction around the Sun. The Sun also spins in the same Result 5 source: books/our-solar-system-and-other-planetary-systems-elizabeth-bell-and-edith-soto.pdf

Wikipedia Retriever for External Knowledge¶

In the cell below, we demonstrate how to retrieve information directly from Wikipedia using LangChain’s WikipediaRetriever, which provides an alternative to local document-based retrieval:

Wikipedia Retriever Initialization: We create a

WikipediaRetrieverinstance with specific configuration:lang="en": Specifies English language Wikipedia as the sourcetop_k_results = 3: Configured to return the top 3 most relevant Wikipedia articles for any query

How It Works: Unlike the FAISS vector store that searches through locally stored and embedded documents, the Wikipedia retriever:

- Sends queries directly to Wikipedia’s API in real-time

- Searches Wikipedia’s vast knowledge base using Wikipedia’s own search algorithms

- Returns entire Wikipedia article pages (or substantial portions) rather than small chunks

- Does not require pre-processing, embedding, or local storage

Query Execution: We perform a search with the question “What is the largest planet in our solar system?”:

- The query is sent to Wikipedia’s search API

- Wikipedia’s algorithm finds the most relevant articles based on title and content matching

- The retriever returns the top 3 article results

Results Display: For each of the 3 retrieved articles, the code prints:

- Content: The full text content from the Wikipedia article (typically the introduction and main sections)

- Source: The Wikipedia URL of the article, showing which specific Wikipedia page the information came from

Advantages of Wikipedia Retriever:

- No Pre-processing: No need to download, chunk, or embed documents in advance

- Always Current: Accesses the latest version of Wikipedia articles in real-time

- Broad Coverage: Leverages Wikipedia’s comprehensive knowledge spanning virtually all topics

- Simple Setup: Requires no vector store, embedding models, or local storage

Trade-offs:

- Internet Dependency: Requires an active internet connection to function

- Less Control: Cannot customize or curate the knowledge base (limited to Wikipedia content)

- Longer Documents: Returns entire articles rather than focused chunks, which may contain irrelevant information

- API Limitations: Subject to Wikipedia API rate limits and availability

Use Case: The Wikipedia retriever is ideal for:

- General knowledge question-answering systems

- Prototyping and development without local data preparation

- Complementing local document retrieval with external knowledge sources

- Applications where up-to-date information from a trusted public source is valuable

This approach can be combined with local vector stores (like our FAISS astronomy database) to create hybrid retrieval systems that leverage both curated domain-specific documents and broad general knowledge from Wikipedia.

from langchain_community.retrievers.wikipedia import WikipediaRetriever

wikipedia_retriever = WikipediaRetriever(

lang="en",

top_k_results = 3

)

query = "What is the largest planet in our solar system?"

results = wikipedia_retriever.invoke(query)

print(f"Top 3 Wikipedia results for the query '{query}':\n\n")

for i, result in enumerate(results):

print(f"Result {i+1} content:\n{result.page_content}\n\n")

print(f"Result {i+1} source:\n{result.metadata['source']}\n\n")

Top 3 Wikipedia results for the query 'What is the largest planet in our solar system?': Result 1 content: The Solar System is the gravitationally bound system of the Sun and the masses that orbit it, most prominently its eight planets, of which Earth is one. The system formed about 4.6 billion years ago when a dense region of a molecular cloud collapsed, creating the Sun and a protoplanetary disc from which the orbiting bodies assembled. Inside the Sun's core hydrogen is fused into helium for billions of years, releasing energy which is over even longer periods of time emitted through the Sun's outer layer, the photosphere. This creates the heliosphere and a decreasing temperature gradient across the Solar System. The mass of the Solar System is by 99.86% almost completely made up of the Sun's mass. The next most massive objects of the system are the eight planets, which by definition dominate the orbits they occupy. Closest to the Sun in order of increasing distance are the four terrestrial planets – Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars. These are the planets of the inner Solar System. Earth and Mars are the only planets in the Solar System which orbit within the Sun's habitable zone, in which the sunlight can make surface water under atmospheric pressure liquid. Beyond the frost line at about five astronomical units (AU), are two gas giants – Jupiter and Saturn – and two ice giants – Uranus and Neptune. These are the planets of the outer Solar System. Jupiter and Saturn possess nearly 90% of the non-stellar mass of the Solar System. Additionally to the planets there are in the Solar System other planetary-mass objects, but which do not dominate their orbits, such as dwarf planets and planetary-mass moons. The International Astronomical Union's Minor Planet Center lists Ceres, Pluto, Eris, Makemake, and Haumea as dwarf planets. Four other Solar System objects are generally identified as such: Orcus, Quaoar, Gonggong, and Sedna. Natural satellites, which are commonly called 'moons', can be found throughout the Solar System and in sizes from planetary-mass moons to much less massive moonlets at their smallest. The largest two moons (Ganymede of Jupiter and Titan of Saturn) are larger than the smallest planet (Mercury), while the seven most massive, which includes Earth's Moon, are more massive and larger than any of the dwarf planets. Less massive than these planetary-mass objects are the vast number of small Solar System bodies, such as asteroids, comets, centaurs, meteoroids, and interplanetary dust clouds. All dwarf planets and many of the smaller bodies are within the asteroid belt (between Mars's and Jupiter's orbit) and the Kuiper belt (just outside Neptune's orbit). The Solar System is within the heliosphere constantly flooded by the charged plasma particles of the solar wind, which forms with the interplanetary dust, gas and cosmic rays between the bodies of the Solar System an interplanetary medium. At around 70–90 AU from the Sun, the solar wind is halted by the interstellar medium, resulting in the heliopause and the border of the interplanetary medium to interstellar space. Further out somewhere beyond 2,000 AU from the Sun extends the outermost region of the Solar System, the theorized Oort cloud, the source for long-period comets, stretching to the edge of the Solar System, the edge of its Hill sphere, at 178,000–227,000 AU (2.81–3.59 ly), where its gravitational potential becomes equal to the galactic potential. The Solar System currently moves through a cloud of interstellar medium called the Local Cloud. The closest star to the Solar System, Proxima Centauri, is 269,000 AU (4.25 ly) away. Both are within the Local Bubble, a relatively small 1,000 light-years (ly) wide region of the Milky Way. == Definition == The Solar System includes the Sun and all objects that are bound to it by gravity and orbit it. The International Astronomical Union describes the Solar System as all objects that are bound by the gravity of the Sun, the Sun itself, its eight planets, and the other celestial bodies which orbit it. NASA describes Result 1 source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solar_System Result 2 content: Planet Nine is a hypothetical ninth planet in the outer region of the Solar System. Its gravitational effects could explain the peculiar clustering of orbits for a group of extreme trans-Neptunian objects (ETNOs)—bodies beyond Neptune that orbit the Sun at distances averaging more than 250 times that of the Earth, over 250 astronomical units (AU). These ETNOs tend to make their closest approaches to the Sun in one sector, and their orbits are similarly tilted. These alignments suggest that an undiscovered planet may be shepherding the orbits of the most distant known Solar System objects. Nonetheless, some astronomers question this conclusion and instead assert that the clustering of the ETNOs' orbits is due to observational biases stemming from the difficulty of discovering and tracking these objects during much of the year. Based on earlier considerations, this hypothetical super-Earth—mini-Neptune sized planet would have had a predicted mass of five to ten times that of the Earth, and an elongated orbit 400–800 AU. The orbit estimation was refined in 2021, resulting in a somewhat smaller semimajor axis of 380+140−80 AU. This was shortly thereafter updated to 460 +160−100 AU, and to 290±30 AU in 2025. Astronomers Konstantin Batygin and Michael Brown have suggested that Planet Nine may be the core of a giant planet that was ejected from its original orbit by Jupiter during the genesis of the Solar System. Others suggest that the planet was captured from another star, was once a rogue planet, or that it formed on a distant orbit and was pulled into an eccentric orbit by a passing star. Although sky surveys such as Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) and Pan-STARRS did not detect Planet Nine, they have not ruled out the existence of a Neptune-diameter object in the outer Solar System. The ability of these past sky surveys to detect Planet Nine was dependent on its location and characteristics. Further surveys of the remaining regions were conducted using NEOWISE and are ongoing using the 8-meter Subaru Telescope. Unless Planet Nine is observed, its existence remains purely conjectural. Several alternative hypotheses have been proposed to explain the observed clustered distribution of trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs). Subsequent discoveries of objects including 2017 OF201 and 2023 KQ14 have challenged the hypothesis, as their orbits are not aligned with the other TNOs and would be unstable if Planet Nine were present. == History == Following the discovery of Neptune in 1846, there was considerable speculation that another planet might exist beyond its orbit. The best-known of these theories predicted the existence of a distant planet that was influencing the orbits of Uranus and Neptune. After extensive calculations, Percival Lowell predicted the possible orbit and location of the hypothetical trans-Neptunian planet and began an extensive search for it in 1906. He called the hypothetical object Planet X, a name previously used by Gabriel Dallet. Clyde Tombaugh continued Lowell's search and in 1930 discovered Pluto, but it was soon determined to be too small to qualify as Lowell's Planet X. After Voyager 2's flyby of Neptune in 1989, the difference between Uranus' predicted and observed orbit was determined to have been due to the use of a previously inaccurate mass of Neptune. Attempts to detect planets beyond Neptune by indirect means such as orbital perturbation date to before the discovery of Pluto. Among the first was George Forbes who postulated the existence of two trans-Neptunian planets in 1880. One would have an average distance from the Sun, or semi-major axis, of 100 AU, 100 times that of the Earth. The second would have a semi-major axis of 300 AU. Forbes' work is considered similar to more recent Planet Nine theories in that the planets would be responsible for a clustering of the orbits of several objects, in this case the clustering of aphelion distances of periodic comets near about 100–300 AU. This is si Result 2 source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Planet_Nine Result 3 content: A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is generally required to be in orbit around a star, stellar remnant, or brown dwarf, and is not one itself. The Solar System has eight planets by the most restrictive definition of the term: the terrestrial planets Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars, and the giant planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a young protostar orbited by a protoplanetary disk. Planets grow in this disk by the gradual accumulation of material driven by gravity, a process called accretion. The word planet comes from the Greek πλανήται (planḗtai) 'wanderers'. In antiquity, this word referred to the Sun, Moon, and five points of light visible to the naked eye that moved across the background of the stars—namely, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Planets have historically had religious associations: multiple cultures identified celestial bodies with gods, and these connections with mythology and folklore persist in the schemes for naming newly discovered Solar System bodies. Earth itself was recognized as a planet when heliocentrism supplanted geocentrism during the 16th and 17th centuries. With the development of the telescope, the meaning of planet broadened to include objects only visible with assistance: the moons of the planets beyond Earth; the ice giants Uranus and Neptune; Ceres and other bodies later recognized to be part of the asteroid belt; and Pluto, later found to be the largest member of the collection of icy bodies known as the Kuiper belt. The discovery of other large objects in the Kuiper belt, particularly Eris, spurred debate about how exactly to define a planet. In 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) adopted a definition of a planet in the Solar System, placing the four terrestrial planets and the four giant planets in the planet category; Ceres, Pluto, and Eris are in the category of dwarf planet. Many planetary scientists have nonetheless continued to apply the term planet more broadly, including dwarf planets as well as rounded satellites like the Moon. Further advances in astronomy led to the discovery of over 5,900 planets outside the Solar System, termed exoplanets. These often show unusual features that the Solar System planets do not show, such as hot Jupiters—giant planets that orbit close to their parent stars, like 51 Pegasi b—and extremely eccentric orbits, such as HD 20782 b. The discovery of brown dwarfs and planets larger than Jupiter also spurred debate on the definition, regarding where exactly to draw the line between a planet and a star. Multiple exoplanets have been found to orbit in the habitable zones of their stars (where liquid water can potentially exist on a planetary surface), but Earth remains the only planet known to support life. Such a habitable zone is complicated by many factors, such as the atmospheric composition (if there is an atmosphere) of the planet; Mars, for example, has the temperature during the day to form liquid water on its surface on the equator, if only the pressure were higher. == Formation == It is not known with certainty how planets are formed. The prevailing theory is that they coalesce during the collapse of a nebula into a thin disk of gas and dust. A protostar forms at the core, surrounded by a rotating protoplanetary disk. Through accretion (a process of sticky collision) dust particles in the disk steadily accumulate mass to form ever-larger bodies. Local concentrations of mass known as planetesimals form, and these accelerate the accretion process by drawing in additional material by their gravitational attraction. These concentrations become increasingly dense until they collapse inward under gravity to form protoplanets. After a planet reaches a mass somewhat larger than Mars's mass, it begins to accumulate an extended atmosphere, greatly increasi Result 3 source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Planet

Hybrid Retrieval: Combining Semantic and Keyword Search¶

In the cell below, we demonstrate a powerful hybrid retrieval approach that combines two complementary search strategies to improve information retrieval quality:

1. Semantic Retriever (Vector-Based Search)¶

We load the FAISS vector store containing our astronomy document embeddings and configure it as a semantic retriever:

search_kwargs={"k":3}: Returns the top 3 most semantically similar chunks- How it works: Converts the query into an embedding vector and finds documents with similar vector representations

- Strengths: Excellent at understanding conceptual similarity and intent, even when exact keywords don’t match

- Example: Can match “dwarf planets” with “small celestial bodies” or “Pluto classification”

2. Keyword Retriever (BM25 Algorithm)¶

We create a BM25Retriever from the same document chunks:

k = 2: Returns the top 2 most relevant chunks based on keyword matching- How it works: Uses the BM25 ranking algorithm (Best Matching 25), a sophisticated term-frequency based approach that considers:

- How often query terms appear in each document

- Document length normalization

- Inverse document frequency (rarer terms are weighted higher)

- Strengths: Excels at finding exact matches, technical terms, and specific phrases

- Example: Will strongly match documents containing the exact phrase “dwarf planets”

3. Merger Retriever (Hybrid Combination)¶

The MergerRetriever combines both retrievers into a unified system:

- Takes results from both the semantic retriever (3 results) and keyword retriever (2 results)

- Merges them into a single ranked list, removing duplicates

- Provides up to 5 total results (or fewer if there are duplicates)

4. Query Execution¶

We search for information about “Explain the concept of dwarf planets” using the hybrid approach:

- The semantic retriever finds conceptually related content about planetary classification

- The keyword retriever finds exact mentions of “dwarf planets”

- The merger combines both perspectives for comprehensive results

5. Enhanced Results Display¶

For each retrieved document, the code prints:

- Content: The text chunk that was retrieved

- Full Metadata: Complete metadata including producer, page numbers, source file, etc.

- Source: The specific PDF file the content came from (useful when searching across multiple documents)

Why Hybrid Retrieval?¶

Combining semantic and keyword search provides the best of both worlds:

| Approach | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Semantic (Vector) | Understands meaning, handles synonyms, captures context | May miss exact technical terms, less precise |

| Keyword (BM25) | Precise exact matches, finds specific terms | Misses conceptual similarity, struggles with paraphrasing |

| Hybrid (Both) | Comprehensive coverage, balanced results | Slightly more complex setup |

Use Case: This hybrid approach is considered best practice for production RAG systems because it ensures you don’t miss relevant information whether users phrase queries semantically (“explain classification of small planets”) or use exact terminology (“dwarf planets definition”).

from langchain_community.vectorstores import FAISS

from langchain_community.retrievers import BM25Retriever

from langchain_classic.retrievers import MergerRetriever

vector_store = FAISS.load_local(

folder_path = "faiss_index",

embeddings = embedding_model,

allow_dangerous_deserialization = True

)

semantic_retriever = vector_store.as_retriever(search_kwargs={"k":3})

keyword_retriever = BM25Retriever.from_documents(documents = chunks, k = 2)

merger_retriever = MergerRetriever(

retrievers=[semantic_retriever, keyword_retriever]

)

query = "Explain the concept of dwarf planets."

results = merger_retriever.invoke(query)

print(f"Top 5 merged results for the query '{query}':\n\n")

for i, result in enumerate(results):

print(f"Result {i+1} content:\n{result.page_content}\n\n")

print(f"Result {i+1} metadata:\n{result.metadata}\n\n")

print(f"Result {i+1} source:\n{result.metadata['source']}\n\n")

Top 5 merged results for the query 'Explain the concept of dwarf planets.':

Result 1 content:

Contents

15 Dwarf Planets 169

15.1 Ceres . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 169

15.2 Pluto . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 169

15.3 Charon . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 169

15.4 Haumea . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 169

15.5 Hi’aka . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 169

15.6 Namaka . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 169

15.7 Makemake . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 170

15.8 Eris . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 170

15.9 Dysnomia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 170

16 Other Objects 171

16.1 Quaoar . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 171

Result 1 metadata:

{'producer': '3-Heights™ PDF Optimization Shell 6.3.1.5 (http://www.pdf-tools.com)', 'creator': 'LaTeX with hyperref package', 'creationdate': '2015-03-15T13:10:03+01:00', 'moddate': '2023-10-09T20:27:12+00:00', 'source': 'books/general-astronomy-wikibooks.pdf', 'total_pages': 341, 'page': 5, 'page_label': 'VI'}

Result 1 source:

books/general-astronomy-wikibooks.pdf

Result 2 content:

planets differ greatly in size and chemical properties. The biggest dispute concerns Pluto, which is much smaller than the

other eight major planets. The category of dwarf planet was invented to include Pluto and similar icy objects beyond

Neptune. But is a dwarf planet also a planet? Logically, it should be, but even this simple issue of grammar has been the

subject of heated debate among both astronomers and the general public.

Key Concepts and Summary

Our solar system currently consists of the Sun, eight planets, five dwarf planets, nearly 200 known moons, and a host of

smaller objects. The planets can be divided into two groups: the inner terrestrial planets and the outer giant planets.

Result 2 metadata:

{'producer': '3-Heights™ PDF Optimization Shell 6.3.1.5 (http://www.pdf-tools.com)', 'creator': 'Acrobat PDFMaker 11 for Word', 'creationdate': '2018-01-17T12:25:30-08:00', 'author': 'Radtke, Trudi', 'comments': '', 'company': 'College of the Canyons', 'keywords': '', 'sourcemodified': 'D:20180117200706', 'subject': '', 'title': '', 'moddate': '2023-10-09T20:19:17+00:00', 'source': 'books/our-solar-system-and-other-planetary-systems-elizabeth-bell-and-edith-soto.pdf', 'total_pages': 421, 'page': 128, 'page_label': '129'}

Result 2 source:

books/our-solar-system-and-other-planetary-systems-elizabeth-bell-and-edith-soto.pdf

Result 3 content:

316 | Our Solar System & Other Planetary Systems

To many astronomers, Pluto seemed like the odd cousin that

everyone hopes will not show up at the next family reunion. Neither

its path around the Sun nor its size resembles either the giant planets

or the terrestrial planets. In the 1990s, astronomers began to

discover additional small objects in the far outer solar system,

showing that Pluto was not unique. We will discuss these trans-

neptunian objects later with other small bodies, in the chapter

on Comets and Asteroids: Debris of the Solar System

. One of them

(called Eris) is nearly the same size as Pluto, and another

(Makemake) is substantially smaller. It became clear to astronomers

that Pluto was so different from the other planets that it needed a

new classification. Therefore, it was called a dwarf planet, meaning a

planet much smaller than the terrestrial planets. We now know of

many small objects in the vicinity of Pluto and we have classified

Result 3 metadata:

{'producer': '3-Heights™ PDF Optimization Shell 6.3.1.5 (http://www.pdf-tools.com)', 'creator': 'Acrobat PDFMaker 11 for Word', 'creationdate': '2018-01-17T12:25:30-08:00', 'author': 'Radtke, Trudi', 'comments': '', 'company': 'College of the Canyons', 'keywords': '', 'sourcemodified': 'D:20180117200706', 'subject': '', 'title': '', 'moddate': '2023-10-09T20:19:17+00:00', 'source': 'books/our-solar-system-and-other-planetary-systems-elizabeth-bell-and-edith-soto.pdf', 'total_pages': 421, 'page': 316, 'page_label': '317'}

Result 3 source:

books/our-solar-system-and-other-planetary-systems-elizabeth-bell-and-edith-soto.pdf

Result 4 content:

220 | Our Solar System & Other Planetary Systems

What are Earth’s core and mantle made of? Explain how we know.

Describe the differences among primitive, igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic rock, and relate these differences to

their origins.

Explain briefly how the following phenomena happen on Earth, relating your answers to the theory of plate tectonics

A. earthquakes

B. continental drift

C. mountain building

D. volcanic eruptions

E. creation of the Hawaiian island chain

What is the source of Earth’s magnetic field?

Why is the shape of the magnetosphere not spherical like the shape of Earth?

Although he did not present a mechanism, what were the key points of Alfred Wegener’s proposal for the concept of

continental drift?

List the possible interactions between Earth’s crustal plates that can occur at their boundaries.

List, in order of decreasing altitude, the principle layers of Earth’s atmosphere.

Result 4 metadata:

{'producer': '3-Heights™ PDF Optimization Shell 6.3.1.5 (http://www.pdf-tools.com)', 'creator': 'Acrobat PDFMaker 11 for Word', 'creationdate': '2018-01-17T12:25:30-08:00', 'author': 'Radtke, Trudi', 'comments': '', 'company': 'College of the Canyons', 'keywords': '', 'sourcemodified': 'D:20180117200706', 'subject': '', 'title': '', 'moddate': '2023-10-09T20:19:17+00:00', 'source': 'books/our-solar-system-and-other-planetary-systems-elizabeth-bell-and-edith-soto.pdf', 'total_pages': 421, 'page': 220, 'page_label': '221'}

Result 4 source:

books/our-solar-system-and-other-planetary-systems-elizabeth-bell-and-edith-soto.pdf

Result 5 content:

many small objects in the vicinity of Pluto and we have classified

several as dwarf planets.

A similar history was associated with the discovery of the asteroids.

When the first asteroid (Ceres) was discovered at the beginning of

the nineteenth century, it was hailed as a new planet. In the

following years, however, other objects were found with similar

orbits to Ceres. Astronomers decided that these should not all be

considered planets, so they invented a new class of objects, called

minor planets or asteroids. Today, Ceres is also called a dwarf planet. Both minor planets and dwarf planets are part of a

whole belt or zones of similar objects (as we will discuss in Comets and Asteroids: Debris of the Solar System

).

So, is Pluto a planet? Our answer is yes, but it is a dwarf planet, clearly not in the same league with the eight major

planets (four giants and four terrestrials). While some people were upset when Pluto was reclassified, we might point

Result 5 metadata:

{'producer': '3-Heights™ PDF Optimization Shell 6.3.1.5 (http://www.pdf-tools.com)', 'creator': 'Acrobat PDFMaker 11 for Word', 'creationdate': '2018-01-17T12:25:30-08:00', 'author': 'Radtke, Trudi', 'comments': '', 'company': 'College of the Canyons', 'keywords': '', 'sourcemodified': 'D:20180117200706', 'subject': '', 'title': '', 'moddate': '2023-10-09T20:19:17+00:00', 'source': 'books/our-solar-system-and-other-planetary-systems-elizabeth-bell-and-edith-soto.pdf', 'total_pages': 421, 'page': 316, 'page_label': '317'}

Result 5 source:

books/our-solar-system-and-other-planetary-systems-elizabeth-bell-and-edith-soto.pdf

Query Expansion for Improved RAG Retrieval¶

In the cell below, we demonstrate an advanced technique called query expansion that uses a Large Language Model (LLM) to enhance user queries before performing retrieval:

1. LLM Initialization¶

We initialize a local language model using Ollama:

ChatOllama(model="qwen3-vl:8b"): Loads the Qwen3-VL 8 billion parameter vision-language model running locally through Ollama- This model will intelligently rewrite user queries to improve retrieval quality

2. Query Expansion Prompt Template¶

We create a specialized prompt template with specific instructions for query rewriting:

- Preserve original intent: Ensures the rewritten query addresses the same question

- Add missing context: Fills in implicit information that would help find relevant documents

- Expand abbreviations and references: Makes vague terms explicit (e.g., “sun” → “Sun’s gravitational force”)

- Make entities and relationships explicit: Clarifies what entities are involved and how they relate

- Include relevant keywords: Adds technical terms users expect in answers (e.g., “Kepler’s laws”, “elliptical orbits”)

- Avoid hallucination: Does not add facts or change the question’s meaning

- Remain concise: Keeps the expanded query focused and factual

3. Query Processing Chain¶

We create a LangChain processing chain that:

- Takes the original user query as input

- Passes it through the prompt template to format the instruction

- Sends the formatted prompt to the LLM for intelligent rewriting

- Returns an expanded, retrieval-optimized version of the query

4. Original Query¶

The user asks: “Explain the effect of sun on planets orbit?”

- This query is somewhat vague and uses informal language (“sun” instead of “Sun”)

- Missing important context about gravitational mechanics, orbital dynamics, and relevant laws

5. Query Expansion Execution¶

The chain processes the original query:

- The LLM analyzes the question and identifies implicit concepts

- It rewrites the query to include explicit terminology and context

- The expanded query might include terms like “gravitational force”, “Kepler’s laws”, “elliptical orbits”, “planetary motion”, etc.

- Both the original and expanded queries are printed for comparison

6. Retrieval with Expanded Query¶

The expanded query is used with the hybrid merger retriever:

- The improved query should retrieve more relevant document chunks because it uses precise technical terminology

- The semantic retriever benefits from explicit keywords matching document vocabulary

- The keyword retriever (BM25) benefits from technical terms that appear in astronomy textbooks

7. Results Display¶

The code prints the top 5 results retrieved using the expanded query:

- Shows the content of each retrieved chunk

- Displays the source PDF file for each result

- Allows comparison of retrieval quality between original vs. expanded queries

Why Query Expansion Matters¶

Query expansion addresses common retrieval challenges:

| Problem | How Expansion Helps |

|---|---|

| Vague queries | Adds specific terminology and context |

| Vocabulary mismatch | Bridges gap between casual language and technical documents |

| Missing context | Makes implicit information explicit |

| Ambiguous references | Clarifies what entities and concepts are involved |

| Incomplete queries | Suggests related concepts that improve retrieval |

Example Transformation¶

Original: “Explain the effect of sun on planets orbit?” Expanded: “Explain the effect of the Sun’s gravitational force on the orbital paths of planets within the solar system, including how this force governs planetary motion according to Kepler’s laws and maintains stable elliptical orbits.”

The expanded version:

- ✅ Capitalizes “Sun” (proper astronomical terminology)

- ✅ Specifies “gravitational force” (the mechanism)

- ✅ Mentions “Kepler’s laws” (relevant scientific framework)

- ✅ Includes “elliptical orbits” (technical detail)

- ✅ Clarifies “planetary motion” and “orbital paths”

Performance Benefits¶

Studies show query expansion can improve RAG system performance by: